Rome is not quite on fire, as in New South Wales with its iCare Scheme, but the signs are there!

What is happening inter-state?

New South Wales

The New South Wales Workers Compensation System (iCare) is in turmoil with Treasury leading the charge to make significant changes designed to improve the scheme’s financial sustainability. The backlash to the proposed changes is currently making the media.

Currently there is a Parliamentary Inquiry into the proposed changes.

Proposed changes to liability and entitlements for psychological injury in New South Wales

Critics of the proposed changes have highlighted the inherent conflicts that arise between Workplace Health & Safety Legislation with increasing requirements to manage psychosocial risk while the proposed changes to compensation legislation will make it more difficult for workers to access care for their mental health.

These conflicts are highlighted in the linked article.

South Australia

South Australia updated its legislation in 2014 and, in 2022, further amendments were required to ensure the sustainability of the scheme, as summarised below.

The Return to Work Act 2014 required that injured workers not classified as “seriously injured” are entitled to weekly income maintenance payments for a maximum of 2 calendar years from the date of first entitlement. This limit applied even if the worker returned to work during that period or had intermittent periods without entitlement. A “seriously injured worker” is defined as someone whose work injury has resulted in a whole person impairment (WPI) of 30% or more. Workers meeting this threshold are eligible for extended benefits,

The Return to Work (Scheme Sustainability) Amendment Act 2022, passed on 6 July 2022, focused on ensuring the financial viability of the Return to Work scheme with Cost Management Measures. These included adjustments to various aspects of the scheme to maintain average premium rates below 2.00%, balancing employer contributions with scheme sustainability.

Victoria

Victoria’s workers’ compensation scheme, WorkCover, has faced significant scrutiny in recent years due to financial strain, rising mental health claims with legislative reforms aimed at ensuring its sustainability.

WorkCover has experienced substantial financial deficits, with a reported $1.6 billion shortfall in the 2022–23 financial year, following a $3.9 billion deficit the previous year. A significant contributor to these deficits is the increase in mental health-related claims, which now constitute approximately 16% of all new claims and account for about 50% of the scheme’s costs . The surge in long-term mental health claims has been attributed to factors such as workplace stress, burnout, and interpersonal conflicts

In response to these challenges, the Victorian Parliament enacted the Workplace Injury Rehabilitation and Compensation Amendment (WorkCover Scheme Modernisation) Act 2024, effective from 31 March 2024. Key changes include:

- Restricted Mental Health Claims: Claims for mental injuries predominantly caused by work-related stress or burnout are no longer compensable unless linked to traumatic events considered typical in the worker’s role .

- Stricter Eligibility for Long-Term Payments: After 130 weeks of receiving weekly payments, workers must demonstrate a whole-person impairment exceeding 20% and an indefinite incapacity to perform any suitable work to continue receiving benefits .

- Increased Premiums for Employers: To address the scheme’s financial instability, employer premiums have been raised, with business groups advocating for reforms to mitigate escalating costs .

In Victoria there have been particular problems within their State Service. Victoria Police has faced staffing shortages, with increased WorkCover premiums due to a rise in mental health leave among officers . Similarly, a parliamentary inquiry into Ambulance Victoria revealed a toxic workplace culture leading to increased WorkCover claims and concerns over service delivery .

The signs in Tasmania

Financial Trends

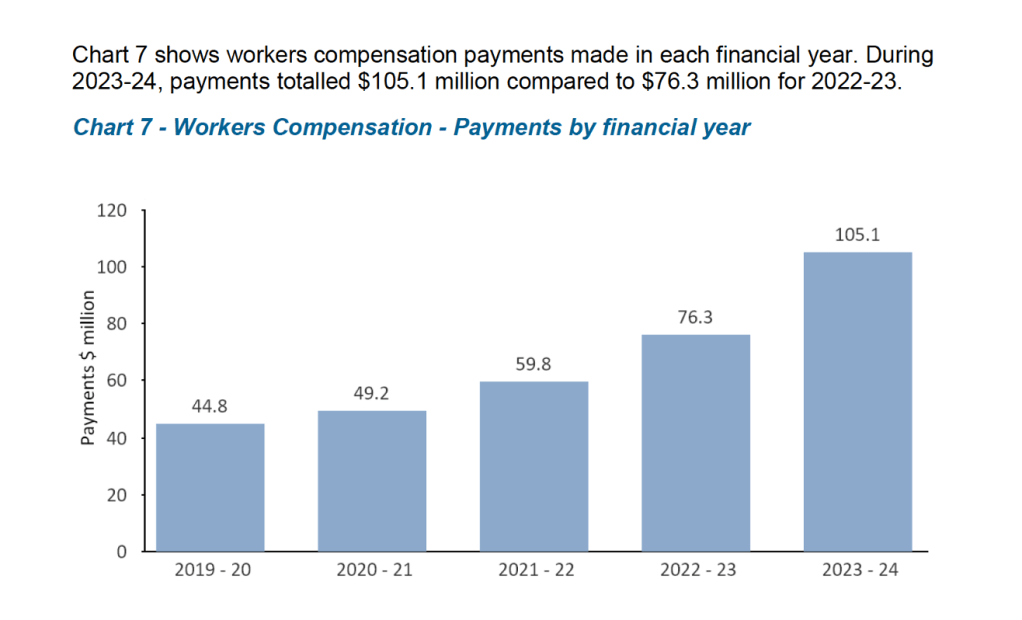

The costs to employers are rising, particularly for State Service Agencies. The State Service is self-insured. The Tasmanian Risk Management Fund publishes workers compensation payments for the State Service. Their most recent Annual Report highlights the alarming trend, a doubling of costs in under 5 years.

Observations from the ‘Coal Face’

The recent Tasmanian WorkCover Board Project, Improving Injury Management Outcomes was focused on the major state service agencies, a response to the recognised concerns about rising claims costs in the State Service. As a practitioner involved in injured worker management and as an independent medical examiner, I have observed adverse trends over my 35+ year career that has included roles as a GP, WHS Manager, Rehabilitation Provider business operator and OEM consultant.

These are my observations:

- There has been progressive loss of Clinical Workplace Leadership in Occupational Health & Wellbeing – for example, there are no longer any of my own specialty of Occupational & Environmental Medicine [OEM] embedded within any private or government organisations. In the 1980’s there were 5 or 6 of us in Tasmania.

- There seems to be an expectation that the legislated workplace health & safety, workers compensation and employee relations systems can address the health care needs of the workforce

- Increasingly, professional resources relevant to health care at work are outsourced, and service providers have become subservient to legally-framed system i.e. followers not leaders.

- Almost exponential growth in ‘for profit’ corporate outsourced services related to claims management, medical assessment, medical treatment, and rehabilitation provision. For example, almost all General Medical Practices, are now corporatised, with only a few owned and managed by medical practitioners.

There seem to be increasing numbers of legal practitioners both embedded within organisations and as private service providers, although it is unclear whether this is a cause or effect of the above trends.

I am particularly concerned about increasing reliance on Independent Medical Assessments/ Reviews [IMEs] by insurers and lawyers (and the quality of those assessments). One of the main tasks undertaken by IME assessors is to assess a party’s liability i.e. it might help the entity decide on whether a particular case belongs in a category where they might have financial responsibility, but is of limited value to the provision of healthcare overall. It just seems to be accepted as a necessary function of the system to protect against fraud, without a full appreciation of the risks, especially from a biased or financially-motivated assessor:

- Is there a psychosocial risk to the worker from the assessment? i.e., what are the effects on RTW outcomes, recovery and requirement for other resources to manage recovery? What is the effect on the worker and more broadly on the health care workers trying to progress treatment?

- What are the consequences of the delay while an IME opinion is obtained? This is becoming even more critical where there are shortages of treaters, making it more difficult for the principle of early intervention to be adopted.

- Have the cost-benefits of the assessment been considered? Could the financial and medical expertise resources utilised on IMEs be directed more effectively?

For example, the Department of Health spent $1.5M on IMEs in 2021, while medical treatment expenses were $1.8M in the same period i.e. nearly as much was spent on IMEs, as on medical treatment. The figures were even worse in 2019, but hopefully better now, although I do not have the current figures, as this type of data is not published.

Why our scheme is no longer ‘Fit for Purpose’

There are rising rates of chronic disease, mental ill-health and co-morbidities in our community. Health management is becoming increasingly complex and expensive. Workers are working longer – well into their 70s. These factors would challenge any healthcare system. There are significant and worsening shortages of various types of health professionals, most notably GPs, Psychiatrists and Psychologists.

There is a divergence between the need to recognise an employer’s responsibility to prevent bullying and harassment and other risks to psychological health (Psychosocial hazards) and the progressive tightening up of compensation entitlements to restrict access to compensation (often the only avenue for psychologically-injured workers). This is what is happening at present in NSW.

Employers argue (correctly) that industrial disputes are becoming ‘medicalised’ as psychological diagnoses leading to compensation and payouts under workers compensation – when they are really employee relations matters.

‘Bolt on’ entitlements for specific classes of workers for additional entitlements complicate the scheme and can provide another mechanism for workers with a grievance to become compensated by a system not intended for that purpose (or create costs to the system for conditions that are not truly work-related).

These types of ‘bolt-ons’ can include:

- Presumptive acceptance of occupational cancers / PTSD for front-line workers

- Employer top up of statutory step downs

- Compensation entitlements for specific classes of employees e.g. jockeys

The Asbestos Compensation Scheme in Tasmania is set up under an entirely different piece of legislation because of long lead time from exposure to the development of disease. This meant workers were not adequately compensated under the Workers Compensation System that existed previously.

There are other occupational diseases, including silicosis, occupational cancers of various types and other diseases with long latency which effectively currently fall into a gap between these existing pieces of legislation.

State Service entitlements for superannuation (particularly the older ‘defined benefit’ schemes) can exert significant effects on workers who have work capacity but not prepared or cannot to go back to their current employer.

The legal involvement to sort out areas of uncertainty in the provision of benefits only damages people further. The system needs to be simple, apply equitably to all workers and take account of acute injuries, chronic pain, psychological injuries, occupational cancers and other long-latency diseases.

Conclusions

There are substantial problems with the current system and the situation is getting worse as reflected by the escalating State Service costs.

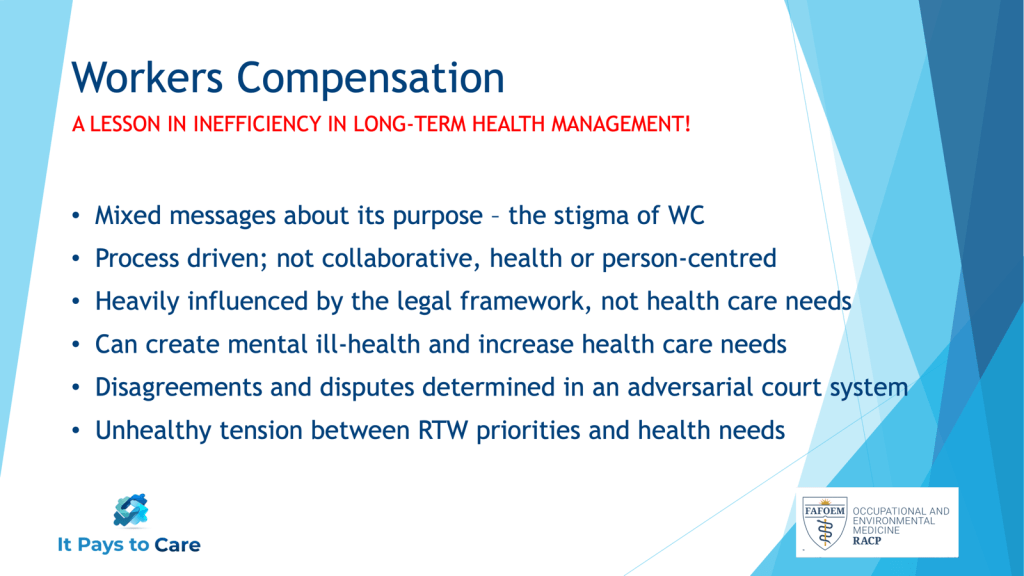

I recently highlighted my conclusions about Tasmania’s Workers Compensation Scheme in a presentation to an important advisory group, as follows:

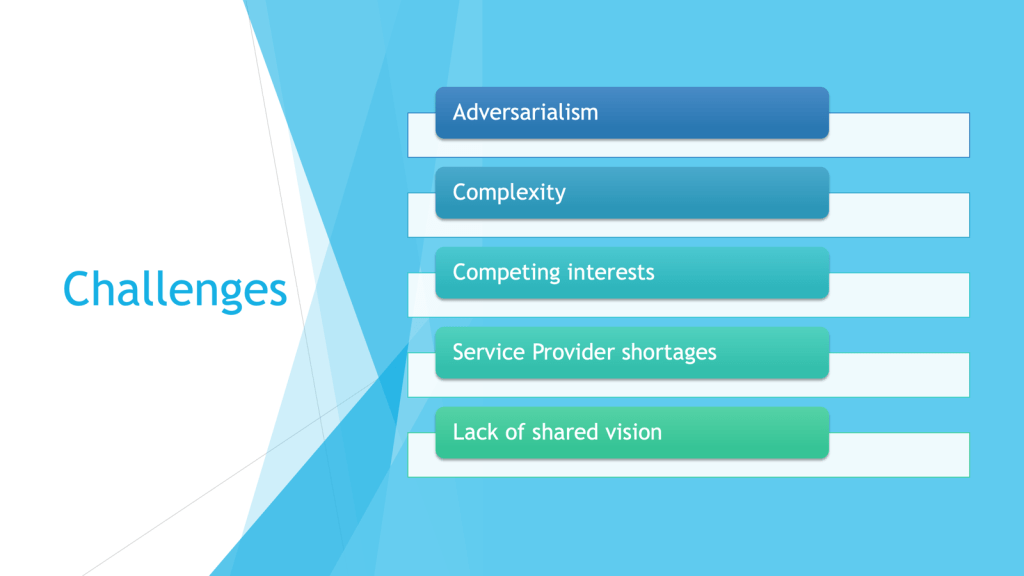

I have also summarised the challenges we face in Tasmania, that affects health care generally, but is particularly relevant to health care for workers:

While the ‘Improving Injury Outcomes in the Tasmanian State Service’ Project produced a set of very reasonable recommendations, I doubt any resulting initiatives will be sufficient to turn the current trends affecting the State Service around and won’t have an effect on the private sector.

I am not confident that existing initiatives can achieve the very fundamental changes necessary.

Solutions

Fundamental reform of Tasmania’s workers compensation system is a priority.

Principles are Important

Radical solutions might look at dismantling of some of the principles of existing schemes e.g. separating out funding of provision of health care e.g. adopting a Private Health Insurance approach, while the compensation scheme itself is responsible for income replacement and RTW. I call this fundamental review process with new system ‘infrastructure’ the ‘SUMMERLEAS’ approach – i.e., making a significant upfront investment in a new approach to Workers Compensation. This is an accepted concept when it comes to ‘bricks and mortar’ developments whether a new bridge, overpass (or even a stadium).

What are the important principles of any new approach?

- A clear vision – What is the purpose of the scheme? – shared by the stakeholders

- Clear definitions – refer my article “Creating Healthy Boundaries”. This includes a review of definitions of work causation. Are the current legal definitions still valid? Is there a more ‘scientific’ approach?

- Incorporate evidence-based, collaborative processes e.g. triaging of claims, early psychosocial assessment, exit mechanisms from the scheme

- Embed ‘It Pays to Care’ Principles

- Measures that reduce the likelihood that employee grievances become ‘medicalised’ as workplace health issues i.e. ensure there are alternative readily accessible processes for such matters

- Incentivise service providers to provide the types of services that evidence shows makes a difference to outcomes – ensuring best use of provides expertise

- Ensure Scheme data informs prevention – the ultimate goal.

There is the important principle ‘Don’t re-invent the wheel’, an important aspect of any review is to consider principles, schemes or processes elsewhere that work effectively. What can we learn from our own MAIB and Asbestos Compensation Schemes, or from interstate schemes that have made a difference or international models?

The Relevance of Complex Systems Theory

To achieve an equitable system that meets as many needs as possible (EQUITY), while utilising limited resources effectively (EFFICIENCY), we need to understand the unpredictability of complex systems. The best approach is to start small and learn what works before a major roll out.

It’s time to start the process of legislative reform now. Not have a rushed knee jerk approach. A workers compensation scheme is an excellent example of a very complex system influenced by political ideology, the historical relationships between employers and employees, current practice and a host of inter-related factors affecting employees and employers and the vested interests of the current array of service providers. There is a two-way relationship between prevention, governed by its own legislative framework and rehabilitation/compensation as well as other legislation and systems that are relevant to income support and retirement e.g superannuation, income protection, motor accident insurance and social security.

To develop a system that addresses all the challenges facing the current scheme will take years, if done properly. Careful planning and consultation will be required to ensure any new approach doesn’t unfairly restrict access to care and compensation for injured workers, risk bankrupting business or government (in the case of the State Service) or leave the community at large to pay (via social security support to disabled or unemployable injured workers) for outcomes that are rightly the responsibility of employers. The concerns of the many vested interests of the current scheme, such as the medical, rehabilitation, insurance and legal systems will need to be worked through, as well.

How & Now!

Responsibility for an effective worker health and wellbeing scheme falls somewhere between the government agencies responsible for Health i.e. Department of Health and Workplace Safety, Rehabilitation & Compensation (Department of Justice). A first step might be an inter-agency Working Group convened by DPAC.

Leadership and care are the key ingredients to get this started. If Tasmania can afford a new Bridgewater Bridge it can invest in new ‘infrastructure’ to support injured workers and employers with a new, evidence-based ‘fit for purpose’ scheme. A healthy, skilled and productive workforce is the key to Tasmania’s future. A health care system for workers is a fundamental ingredient to such a workforce.

Tasmania, as a small state, has a unique opportunity to get this right. The various stakeholders can all work together more easily in a small jurisdiction – they already know each other, but such processes take time. The evidence tells us the principles and can guide the development of necessary processes.

Lets start now and get it right for everyone!